Final assembly is an exciting and tense time; you really feel the "90% done; 90% to go" syndrome. You are so close, yet so far away from completion. You keep thinking of all the details in so many different categories that still need to be done and it can still feel overwhelming. What's worse is when you start tackling a task and realize you actually should have done it long before final assembly. This is going to be one of those blog entries that I hope will help other homebuilders avoid my mistakes. Just like that un-routed trim cable last month, I'm continuing to find tasks that are now much harder to accomplish than they would have been if only I had a total grasp of the ideal building sequence for all the components, not just the major ones.

After repairing the aileron trim system, I removed the flaps for painting. A 10' length of electrical conduit (left over from the hangar lighting) was cut in half; the suspension bolts used when painting the ailerons were modified to fit the conduit ends and the assembled conduits were zip-tied to the flap spars. The same hanging system used for the ailerons worked for the flaps and they were painted in the same manner, with the addition of the red NO STEP lettering on the top inboard ends prior to spraying the clearcoat.

The flaps were returned to the hangar and hung on the wings after applying Teflon anti-chafe tape on the underside trailing edge of the wing top skins. The flap actuating pushrods were connected to the flaps and the actuation weldment in the cockpit. After checking the circuits and recharging the battery, flap deployment and retraction was tested and the travel was good. All connections were tightened, torqued and sealed.

I switched my attention to the wingtips. A trial fit revealed that the attachment nut plates were mostly well aligned with the existing dimpled holes in the wing skins and the aft edges lined up well enough that wing tip trailing edge modification would not be necessary. The wing tip ribs were fitted to the aft ends of the wing tip openings and clamped in place. The two aftmost rivet holes were match drilled in each wing tip and rib to set the rib location. The wing tips were removed and rows of the remaining rivet holes were match drilled in the top and bottom of each wing tip and rib. The holes and edges of each rib were deburred. I brought the ribs back to the shop and prepped them for paint along with the wing inspection covers. All parts were wash primed and primed; the outsides of the inspection covers were sprayed with neutral gray basecoat and clearcoat.

While the paint dried I installed the landing/taxi and nav/strobe lights in each wing tip. Like a lot of final assembly tasks, this seemed much more difficult than it was at the end of fabrication. I studied my wiring schematics and relocated the wire labels before cutting the lighting wires to length. The correct pins were crimped onto the wires and assembled into the Molex connectors, including the tail strobe. I wondered how much I would end up regretting my choice to assemble some of the fiberglass parts unpainted to save time before achieving airworthy status. But the goal of flying in 2021 remained strong; I knew painting the remaining unpainted parts in the spring seemed easy in foresight. I also knew I wouldn't feel that way next spring... but down the road I went, literally skipping all the way. The painted parts were brought back to the hangar; the wing tip rivet holes were countersunk and the ribs riveted in place. Wire routing was checked before the wing tips and tail strobe were mounted to the wings and rudder. Lighting tests were conducted with satisfactory results. After conferring with Ted Gauthier I decided to remove the wing tips, secure the wiring to the outermost wing rib and wrap the connectors with PVC tape to prevent the wiring from chafing on the interior of the wing tips. Additional lighting and flap tests were captured on video and shared on my YouTube channel; see link below.

Van's RV-8 Lighting and Flaps Testing 210922

Van's RV-8 Lighting and Flaps Testing 210922 Moving to a few smaller final assembly tasks, the brake pads were reinstalled, the bolts torqued and sealed and the cotter pin was secured in the wheel nuts and axles. Most of the jam nuts on the control pushrods were checked, torqued and sealed.

I was convinced by several fellow builders that it would be wise to reconnect the aileron trim system before first flight. Of course I had already installed the forward cockpit floor. Sigh... just another example of following my urge to complete an assembly before it was prudent. I knew if I was going to reconnect the aileron trim springs I had better do the best possible job of securing the actuation cable in the Adel clamps. The floor was removed, along with the aileron trim lever panel and the attached cable. After a lot of pondering, I decided to wrap safety wire tightly around the cable on either side of the Adel clamps at each end. Combined with the clamping grip of the Adel clamp, that should keep the cable from moving back and forth in the clamps. The panel, cable and springs were reinstalled and adjusted and the floor reinstalled. The aileron trim should now function as designed; I just wish it had been a better design.

A few more easy final assembly tasks were done. A missing cotter pin was put through the aft stick pivot bolt and castle pin. The tailwheel chains were safety wired to the forward attachment clips. The flap actuator wires were bundled and secured in split conduit in a manner that would allow full motion of the actuator without stressing or chafing the wires. I realized I had forgotten to check the jam nuts on the control pushrods inside the control column between the forward and aft control sticks. I checked them and was glad I did. I discovered one loose jam nut and a temporary nut on the forward control stick rod end bolt. The temporary nut was replaced with a stop nut, all nuts were torqued and sealed and the front seatback and cushions were reinstalled.

It was time to face one of the jobs that I should have done much earlier: the empennage fairing. Again I found myself in the position of wishing I had done things in the correct order. I was in such a hurry to get the empennage assembly finished I completely forgot about drilling out four temporary blind rivets and tapping the lower fairing screw holes in the longerons. It would have been a very simple job without the empennage in place. The holes are now tucked underneath the horizontal stabilizer; there's just barely room to use the angle drill to remove the temporary rivets and the standard tap T-handle couldn't be used on the aftmost holes. After removing the rivets I managed to tap the three forward holes on each side using the stock sliding-bar T-handle. Examining the handle got me thinking of a possible solution but I didn't want to ruin my handle by modified it. I went to the local Ace Hardware to buy a replacement tap handle and second 6/32 tap and was faced with a marketing absurdity. You can get both... but the jaws of the smallest tap handle they sell won't close close tight on the square shank of the 6-32 tap. They even sell a combo pack of four taps and a T-handle... even though the supplied handle will not grip the smallest tap! Totally ridiculous. I even had a store associate open a package and try to make it work on the 6-32 tap; he ended up ruining the handle in the attempt. He apologized, also marveling at how absurd that was. I bailed from Ace and went to another nearby tool store; they had a slightly different style handle that looked like it would work. I modified it by tapping out the T handle and drilling a hole into the back side of the handle that I tapped for a 6-32 bolt, leaving the last couple threads shallow. The bolt tightened up well in the tapped hole and I used a hammer and punch to damage the exposed bolt threads in the handle hole, assuring that the bolt would not come out. With this modified tap tool I was able to use a socket screwdriver and a socket with a pivot handle to tap the remaining holes. Very fiddly, but much better than dismantling the empennage. After tapping, the holes were machine countersunk. The lower fairings were final drilled #30, dimpled for flat head screws and temporarily installed. This forced me to face the next unknown and undone job. The upper and lower empennage fairings both require nut plates to be riveted into the aft top skin for mounting screws. The installed empennage and finished aft fuselage conspire to make access to that portion of the inner skin very difficult to access and install a nut plate. There are a few different ways to approach the problem. Dave Pohl supplied a hefty magnetic stick that may make it possible to hold the nut plate against the skin to get a screw started; blind rivets could be used to secure it from outside. That bridge will be crossed once the fairing pieces are finished. That's the big lesson here, folks: get all of your fairings finished and fitted LONG before final assembly. You'll be glad you did.

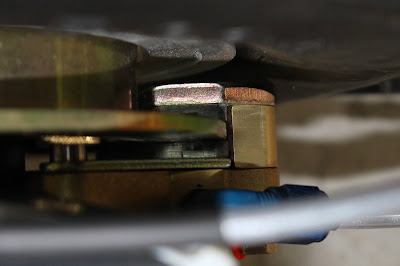

It was about time I filled the brake lines and bled the brakes. Research on VAF revealed some good strategies for this job. I bought a 1/2 gallon garden sprayer pressure pot, some tubing and adapters. A length of tubing was attached to the sprayer wand; another length was attached to the top of the brake fluid reservoir and run down into a catch tank. I had noted the Mil-spec for brake fluid from the Matco brake manual but couldn't find any equivalents at local auto parts stores, so I borrowed some Aeroshell 31 hydraulic fluid from Dave Pohl and filled the pressure pot about halfway. The pot was pressurized; the wand hose was slipped onto the right bleed nipple; the nipple opened 1/2 turn. When the wand trigger was squeezed, pressure forced the fluid from the pot upwards into the system, eventually bleeding out the top of the reservoir and into the catch tank. It was a very easy process, except for when the hose came off the nipple and made a mess. The process was repeated for the left side and soon the system was full with no bubbles coming through the hoses and none visible in the cockpit tubing. I tightened the bleed nipples, disconnected the hoses and allowed the system to set for a half hour. An inspection revealed some bubbles visible in the cockpit tubes and a small drip under the left caliper. The system was bled again and the brakes tested in the cockpit. Both pedals felt mushy and the right pedal was making a suspicious "slishing" sound when pressed. I climbed out of the cockpit to find a big puddle underneath the right gear leg, and my heart sank. Fluid had been leaking from the worst possible place: the threaded AN fitting screwed into the top of the gear leg. I had read about this happening to other builders with the same Grove airfoil gear legs and prayed it wouldn't happen to me, but those prayers were in vain. With my stomach in knots, I drained the system, went home and dove into VAF looking for solutions. (do a search on VAF for "brake leaking" and you'll find the thread)

The location of the fitting made it seemingly impossible to remove; there was not enough clearance between the compression end of the fitting, the gear pocket opening and the cockpit floor above to allow the fitting to rotate and unscrew. Some builders advocated the removal of the gear leg to re-tap the threads. Mounting the gear is one of the most difficult jobs an RV-8 builder has to face and I couldn't bear the thought of having to remove a gear leg and reinstall it, especially with the aircraft almost completed and currently standing on the gear. Other builders found a way to cut off the compression end of the fitting, remove it and replace it with a more compact brass elbow fitting, using different tubing for the cockpit connection. Since aluminum and brass are dissimilar metals and joining them can cause electrolysis and corrosion, this didn't seem like a good alternative to me. Looking closely at the clearance issue, it appeared that I could relieve the edge of the gear pocket opening and stretch the aluminum floor skin upward enough to unscrew the fitting without cutting it. I shielded the tube area of the pocket from aluminum debris and nibbled, ground, cut and sanded a notch in the pocket edge skin until there was enough clearance. I used a socket screwdriver handle and mallet to deform the upper skin enough to swing the fitting; I wasn't worried about the deformation as it would be hidden inside the gear tower. The access was still tight and an angled open end wrench would be needed to rotate the fitting; I knew I had an angled wrench set, but they all looked too small. I did some online shopping and found some, but availability and cost was prohibitive. Dave Pohl came to the rescue with a pack of ignition wrenches that were sized up to the 7/16 required; I later found out that I had an identical set buried in my toolbox. I also had to modify a 9/16" 12-pt. box end wrench to detach the brake line from the flared end of the elbow fitting. I managed to get the fitting off; it was cleaned, more Permatex #2 sealant was applied to the threads and the fitting was reinstalled and tightened one extra turn. The brake system was refilled and tested; the right side was still leaking, albeit more slowly. The next morning I bought a new fitting, went to the hangar and looked at the leak, which appeared to have stopped. Another brake test revealed that not only was the right side still leaking, but the left side now felt soft. I removed the right fitting, cleaned the gear leg threads thoroughly and inspected them with a borescope (inadequate) and an inspection mirror (adequate). While I was underneath the fuselage I pulled the cover off the left gear leg pocket and checked the gear leg. Sure enough, the left side fitting was now leaking in the same manner as the right. Another punch to the gut.

I sought out additional consultation with the PTK gang and the VAF forum. I was beginning to suspect that the Permatex #2 sealant was less than ideal for this application. It wasn't designed to withstand the pressures generated in a brake system and it appeared to be at least somewhat soluble with the Aeroshell 31 fluid. More research and consultation with Hieu Nguyen, Aeroshell's Regional Technical Manager, gave me some good information to use in choosing an appropriate thread sealant. I chose Loctite 567 thread sealant for this application because of it's compatibility with the fluid and its superior pressure retention properties; other builders have also recommended it. Regarding the threads, I had to admit that even with the extra turn and tight fit, there still may not have been enough thread engagement to make a good seal. I needed to chase those 1/8" NPT threads a bit deeper... but how? I refused to remove that gear leg to do it, and the standard tap wouldn't fit in the space. I took some measurements of the working space available, the depth of the threaded hole and the specs of the tap, fitting and hole threads and realized that a modified tap might work. I called the St. Pierre Inc. machine shop and discussed the situation with them. Modifying the tap might be difficult because of the hardened material. I had already run a brass plug in and out of the hole; maybe I could use a galvanized steel plug with slots cut across the threads to use it as a self-tapping plug to extend the threads a bit. I got a couple steel plugs and my standard tap and brought them to the machine shop. We determined a good way to grind new flats onto the shank that would fit a 5/16 open end wrench. The excess shank would be cut off and I would have the ideal tool for the job. They were able to do the work while I watched and took photos and video. I left the machine shop with a big smile on my face; I had my tool much quicker than expected and now I was ready to do a proper fix.

Tap Mod 210930

I prepared the gear leg for tapping by detaching the lower brake line from the bottom fitting and blowing any remaining fluid or contamination out of the gear leg passage with compressed air from the bottom to the top, with a vacuum nozzle suspended at the upper threaded hole. The modified tap was lubricated with cutting oil and screwed into the existing threads. As the threads began to cut I felt sort of a pulsation in the cutting action; I'd feel resistance that would ease up, then get harder, ease up, get harder etc. I don't have a lot of experience cutting NPT threads, but to me it felt like the original threads weren't cut perfectly straight into the hole. The lightening of resistance was felt when each flute of the tap was aligned with the closer hole wall. I ran the tap in as much as I dared, which I guessed was about 1-1/2 cutting turns before measuring the protruding length, removing it and cleaning the fresh threads with folded pipe cleaners soaked in isopropyl alcohol and blowing compressed air through in both directions to clear any remaining chaff. I ran a steel plug into the threads, cinched it, removed it and checked thread engagement, which appeared to be improved. The right gear pocket was covered to keep the area clean while all the necessary operations were done on the left side: trimming, relieving, removal, cleaning, chasing, cleaning. When both sides were ready, the NPT threads on two new fittings were coated with Loctite 567 thread sealant; the fittings were screwed into the fresh threads, tightened and clocked correctly. Measuring the fittings indicated that I may have gained two threads of depth on the left and one thread of depth on the right, with better threads and sealant. All other compression fittings on the gear legs were checked, torqued and sealed. Surely this would be the end of the leaks.

It was recommended that the sealant be allowed to cure for at least 24 hours to maximize the seal before exposing the threads to pressure. That worked out pretty well because it was time for me to head to Texas to get my RV-8 transition training with Bruce Bohannon. I'll give a detailed account of that trip in a separate blog entry to follow this one, but I will say it was one of the truly great flying experiences of my life. I'll give you just one teaser photo here:

I returned to the hangar after eleven days off and got back to work. While I was in Texas, the Ultimate Gust Lock I ordered from Anti-Splat Aero had arrived. I watched the set-up video on YouTube again before attempting to fit it to my aircraft. I was disappointed to find that it was designed for RV-8 aircraft with the sliding adjustable rudder pedal configuration. I had built my aircraft with the ground adjustable pedals; the gust lock ran out of adjustment travel prior to getting into proper position. I called Anti-Splat Aero and described my situation. Allan Nimmo called me back and we discussed the situation in detail. He asked me to send him an email with the photos I had taken and he promised to fabricate a new stick holder bracket with a longer adjustment tube. The email was sent on October 12 with another photo sent on October 13; I await his reply. Anti-Splat Aero has a good reputation for customer satisfaction; I look forward to being a satisfied customer.

Dave Pohl had borrowed my brake fluid pressure pot while I was in Texas and I wasn't quite ready to test the brakes yet, so I worked on fabricating supports for the forward baggage door. There are a lot of different ways you can design a support to hold the baggage door open; most involve articulating or spring-loaded single support struts. I've always thought that the shape and weight of the baggage door could be very easily pushed around in ways that would damage the door, the hinge or the edge skins. A single strut isn't stout enough to prevent such movement. The door should have something substantial to hold it firmly in the open position; something secure that would be unaffected by gusty winds or accidental bumps. I thought about having a support strut on both sides of the bottom of the door that would attach to the opening sides or the right longeron. Designing folding struts would be ideal but trying to figure out the geometry would be very difficult. The two struts would need to be different lengths operating at different angles to match the positions of the door when open and closed. Mocking up folding assemblies wasn't possible; with the door shut there is no access to the inside of the door except through the footwell at an unworkable angle. My design would have to use rigid struts that would be assembled onto the door when open. The baggage door latch pins are hollow tubes; when the door latch is retracted the latch pins are withdrawn until the ends recede into the middle of the snap bushings. The opening in the tube ends and the exposed snap bushing inner surface combine to make an ideal two-step receptacle for a support pin which I had actually drawn out with accurate dimensions long ago. The pins would have a tapped hole in the center that would fit a 6-32 screw to attach the pins to the struts. When I was at St. Pierre having the tap machined I also submitted my drawing of the pins. They said they could machine them out of mild steel and have them ready in a few days. Upon my return from Texas I picked up the pins and got to work on fabricating the struts out of 1/2" aluminum angle. The upper ends were trimmed to fit around the inner door structure and the outer diameter of the pins. Screw holes were drilled in the top of each strut and the pins were attached with screws, washers and Loctite. I assembled the struts onto the latch pin holes and pondered the best way to secure the struts at the bottom. I chose to use the engagement holes in the existing latch blocks on the firewall and bulkhead as anchor points. 1/2" lengths of nylon tubing would fit in the holes; 10-24 screws would grip the tubing and secure it to the bottom of the struts. Bottom hole locations for each strut were laid out, drilled and tapped to accept the 10-24 screws. The screws were secured to the struts with Loctite and the tubing sections were twisted onto the exposed threads of the screws. This worked out very well; the struts held the door very stable in the correct stress-free position. Now I had to figure out how to hold the struts firmly in place. This is complicated because the top of the struts need to be pulled together for the machined pins to stay in the snap bushings, but the bottom of the struts need to be pushed apart for the plastic pins to stay in the latch blocks. There are a lot of different ways to do this, but the simplest is to use springs: a tension spring to pull the tops together and a compression spring to push the bottoms apart. Finding the top spring was easy; although the 13" length requirement was longer than most available springs, I found two springs that I linked together for the perfect sprung length. Curt Martin supplied a small length of plastic hose that fit over the springs and covered up half of each spring and the center section where they are linked. The springs attach easily to small holes in each of the struts and hold the struts in place on the baggage door securely. The bottom spring was more problematic. I couldn't find the right size and length compression spring; combining springs wouldn't really work for that application. Then I thought of an even simpler solution: a 13" length of aluminum tubing could be flared at each end; the flares would fit over the bottom pin screw heads. The tube could be flexed, put in place over the screws and bent back straight, holding the bottom pins firmly in the latch blocks. A little inelegant, but functionally ideal. The parts need to be painted and I may eventually replace the tube with the right length of compression spring, but for now I've got my solution.

With the brake fluid pressure pot back in the hangar, I got everything prepared, crossed my fingers and began refilling the brake system for the third time. The fill hose popped off the nipple again, spilling more fluid. Damn, that's frustrating... and now I'm running low on fluid. Got the system filled and bled; everything's looking good; let it set for an hour; check the fittings. Left one is dry and clean. Right one shows a tiny bit of fluid on the paper towel... was that somehow residual? Wipe it off, check it later. Another tiny bit of fluid. Damn. Get in the cockpit, check the brakes. Left one solid; right one soft. Damn. Climb out and check: fluid on the ground. DAMN. I cannot believe I'm still stuck in Grove Airfoil Gear Hell. I decided to test the brake and record the leak on video so I can see exactly what's happening here. Set up the Canon camera on the tripod under the fuselage; get the lighting right; set the focus and turn off the autofocus; start the recording; get off the floor and into the cockpit. Call out the steps verbally to slate the video, and test the right brake three times. Get out of the cockpit, stop the camera and check the video. Holy DAMN... it's worse than I thought. Still not as bad as the very first leak, which was actually squirting... but way worse than I expected. I sat down in my comfy hangar office chair and tried to recover from yet another punch in the gut. I. Am. So. Tired. Of. This.

It was early afternoon; I had time to drain the system, pull the fitting and re-tap the hole again... but I just didn't want to do it. I was tired; mentally and physically drained. After experiencing the high of the transition training, to come home and get the builder-gut-punch again... I was very, very tired. I started draining the system before getting in my car and going over to Echo row to see if any friends were around. Ted and Mike were at Ted's hangar and I commiserated with them for a few minutes before going home, doing some bookkeeping and generally trying to distract myself and relax. As I began to calm down, I knew I couldn't let the day end like this. I told Amy I would probably go back to the hangar and fix it better this time; don't wait for me for dinner. She understood. I ordered more Aeroshell Fluid 31 before heading back to the airport. As I pulled up to the hangar I saw one of my neighbors hanging out at the end of the row; his friends had their airplane out and flying and he was watching planes in the pattern and listening to the tower awaiting their return. It was a nice evening and I was in no hurry to walk back into the hangar, so I walked over and we talked a bit. He wanted to take a look at my situation so we went inside and he got underneath the gear and checked it out. He's a car mechanic with a lot of experience; we talked about NPT taps and fittings and he gave me some suggestions before heading back outside while I got back to work. I disassembled the right side as before, following the same procedures. But this time I ran the tap in two more full turns. It got quite tight, but I was careful and the threads looked good after I cleaned them up. I cleaned the fitting very thoroughly in and out, coated it very carefully with Loctite 567 and reinstalled it. It went in well and this time I got it in TIGHT, just barely able to get it clocked in the correct position. Before cleaning, the fitting showed it was previously screwed in about 5 threads. After this last tightening, photos revealed that the fitting was in 8 threads. The tubing was reconnected and the assembly left to cure. It won't be refilled until the new stock of Aeroshell 31 fluid arrives next week.

Since then, the only progress I've made on the airplane is to begin trimming the fiberglass upper empennage fairing. That was only one hour of work, so I'll hold off on describing that until the I post the next progress report. I want to get this published and get to work writing the transition training post next. It also occurs to me that I haven't yet described my return to Canada, flying the Chipmunk and the FlightChops RV-14; I'll have to put that in the next post as well. So I guess I've set you up with some cliffhangers... you're just going to have to Stay Tuned!

No comments:

Post a Comment